I’m at two opposing points of view and attempting an impossible reconciliation, somewhere in the art versus design stream; creative freedom versus practical operation. I also have an infatuation with attempting to build bridges between dichotomies [shrugging emoji].

The good news is that after defining the purpose, theory and some assumptions of the WeWork case study, I’ve come to a method. The current plan is to briefly analyse a few common business models of tech companies and of architecture practices, then compare with what I can learn about WeWork. Do you think I’ll get some good insights from there?

But back to dichotomies. Part of the UXer’s role is to navigate the often opposing aspects of the users’ experience. Where there is only one end-user, this can be fairly straight-forward, but those projects are rare and typically private. Multiple end-users make designing the UX more challenging. And individuals are notoriously, well, individual.

This gets me thinking again about architecture’s obsession with the object. For the designer, the urge for creative freedom can be overwhelmingly constrained by every other part of a design process. Perhaps this leads to a need for controlling a design at the expense of anything that makes that too hard – like a user. It seems to me that within architecture (from my newcomer’s perspective), the focus is on how the building affects the user’s experience and behaviour: the external permeating the internal. Through materials, the architect orchestrates an experience to impose on and engage the user; to stimulate reactions; to effect the user. Sure, but is it just me or do I detect a sense of over-dramatic impending doom about this? People are tired of fetishised, ‘marketable’ architecture.

How architecture is informed must change, and the processes and methods must evolve. What influences space and experience must be given equal validity to the final design of a building. This could be better achieved by reversing the focus: the internal permeates the external; metaphysical determining the physical.

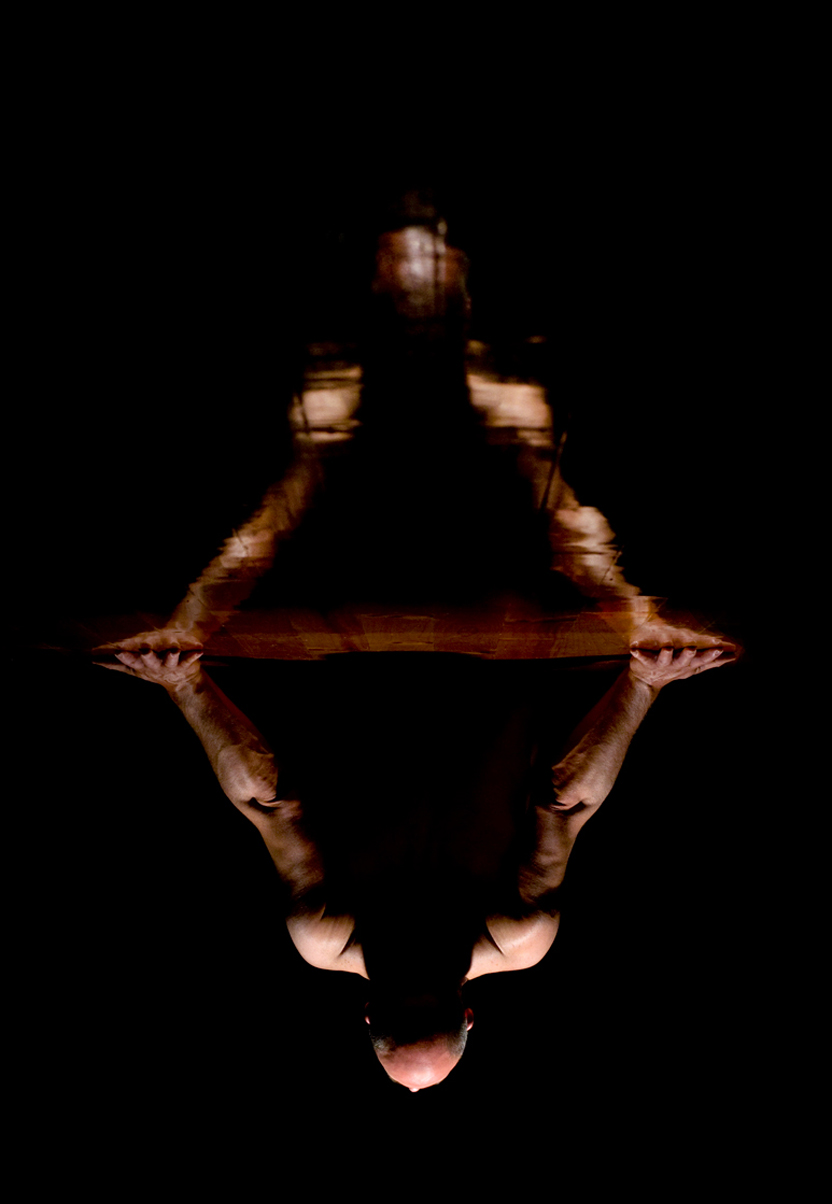

Users are people, and we need healthy spaces to function. Our life needs buildings that are designed, modified and constructed to cultivate healthy space (which, by the way, extends to a healthy planet). In truly considering what users need, first broadly, then specifically, and in parallel with what we already know about how space influences users, we shift to a process that empowers designers to properly integrate our tangible, physical world with the sensual and emotive. In fetishising the experience, the architect becomes the sensualist.

This is exciting, scary, even dangerous territory. It can explore how light and air delight our senses, but can also mean navigating discrimination, trauma, and oppression. It requires an amount of self-actualisation on the architect’s part, a responsive concept, a vast amount of research, analytical processing of that research, and collaboration with other disciplines; out of which will come the design.

This idea of the sensualist architect appears as a strong theme throughout my own research. A UX perspective provides an open and analytical process integrating both bodily and bodiless experiences – please let me know if these ideas remind you of more ideas and reading material. The opinions and criticism I hear around architecture’s obsession with the sublime and ineptitude of codifying it seem unnecessary through a UX lens. There can be method in madness.

Photograph used with permission by Tony Lin, Playing with Shadows.